The evidence shows a strong link between leg function and arm injury.

Article by Dr. Evan Ingerson, DPT of Mend Physical Therapy, Supporting sponsor of the BCC

Images courtesy of Mend PT

It may not seem obvious, but weakness in our hips can lead directly to shoulder pain while climbing. Because climbing requires the use of all extremities simultaneously, impairments in one region of the body almost always have a direct impact on the other extremities. One of the most common, but seldom recognized, patterns is the relationship between the shoulder and the opposite side hip.

In this article we’re going to discuss how the hips are used in climbing, the role our hip strength can play in shoulder injuries, and show you how you can test your own hip strength (and how to strengthen your hips if you need it!).

The relationship between opposite side hip and shoulder (example: right hip and left shoulder) has been studied extensively in the overhead athlete literature, particularly in baseball pitchers, javelin throwers, and cross fitters. Research has shown a clear and consistent link between hip weakness and the development of impingement, rotator cuff, and labrum injuries in overhead athletes.¹ ² ³ The commonalities between these sports and rock climbing is that all require generating power through our upper bodies by leveraging stability through the lower extremities on a fixed surface.

One way movement experts think about the relationship between different body regions is using the term “chains”. These are groups of muscles that are neurologically and anatomically linked and are key to climbing performance and climbing rehabilitation.

The lateral chain is made up of the deltoid, external/internal obliques, latissimus dorsi, hip abductors, and peroneal muscles. The hip abductors push the legs outward (away from each other).

The medial chain is made up of the pectoralis major, internal/external obliques, and the hip adductors. The hip adductors pull the legs inward (closer together).

The posterior chain describes basically all of the muscles on the back side of the body and has been written about previously on TrainingBeta. These muscles are the thoracic and lumbar erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and calves.

The anterior chain refers to the muscles on the front side of the body and is the most commonly trained chain among climbers. This includes the pectoralis major, rectus abdominus, hip flexors, quadriceps, and tibialis anterior.

The muscles we’re going to pay the most attention to in this article are the hip abductors and adductors which are part of the lateral and medial chains, respectively.

Here are two very common patterns seen in the clinic:

A climber has reached a plateau with their climbing performance, especially with powerful shoulder movements. They’ve been training optimally and effectively strengthening their upper body, but something is missing. Often it is a weakness in the medial or lateral chains.

A climber has chronic shoulder pain or finger pain. Their strength is great, range of motion is full, and they’ve done everything their PT has told them to do. But something is missing. With these clients it is common to find significant weakness in the medial or lateral (or both!) chains and this is the underlying impairment causing their continued pain.

Let’s take a look at how the medial and lateral chains are used in climbing, particularly looking at the hip muscles.

When reaching upward while using a gaston or small crimp, notice how the opposite side (left) hip adductors and the same side (right) hip abductors are used to generate stability and power. You can see the same relationship between opposite side hip adductors and same side hip abductors during a side pull or compression movement

Some movements require the use of both adductors simultaneously.

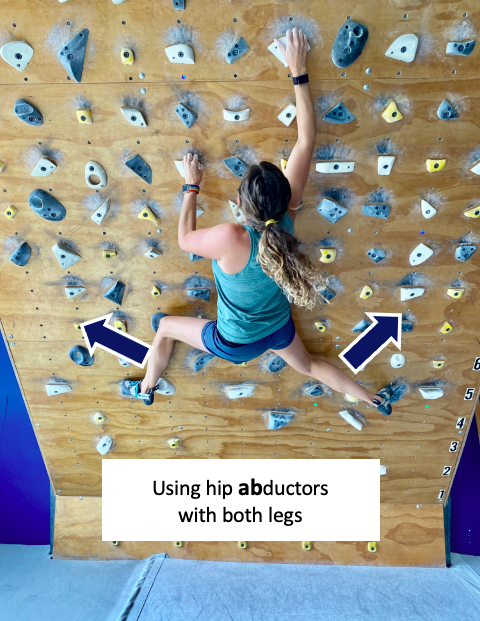

And some movements require the use of both hip abductors simultaneously.

You can think of all the joints and muscles in your body as a big assembly line.

One weak point in the assembly line will force the other parts to work harder to accommodate, leading to increased injury risk. The most common joint to get negatively affected is the shoulder and the elbows and fingers are also commonly affected.

If you’re someone who has been dealing with chronic shoulder, elbow or finger pain, consider assessing your hip strength to see if there are other hidden contributing impairments at play.

For those who are not in pain but have seen a plateau in your climbing performance, try these medial and lateral chain strength tests to see if you could be getting more out of your core to help you get past that cruxy move.

Try this evidence-based test of your hip/core strength.

This is called the Bunkie Test which was designed to test the strength of the different muscular chains of your body.⁴ This is a timed test where the participant holds the position for as long as possible, then compares their times to established expected values as well as comparing the participant’s right to left sides. This test is designed to compare the four primary chains of the body. For the purpose of this article, the most important chains to test are the Lateral and Medial Chains.

Testing procedure:

Establish the starting position, making sure you’re using proper form (see below).

Hold the position for as long as possible, maintaining proper form throughout.

The test ends, and the timer stops, the moment you can no longer maintain the proper position OR if you experience pain that you are uncomfortable pushing through.

Record the time for each position on the right and left sides.

Based on the original study the expected score for each test is 40 seconds and a difference of right side compared to left side greater than 10% is considered a significant finding.

Tip from the PT:

The score of 40 seconds was established based on an “active population”, not for climbers specifically. Consider the grade of climbing you do and how much core strength rock climbing requires. Most climbers would benefit from having these scores be greater than 60 seconds at minimum!

Lateral Chain Test: hold your body in a side plank position with one leg on the step and the other leg elevated. Perform on both sides.

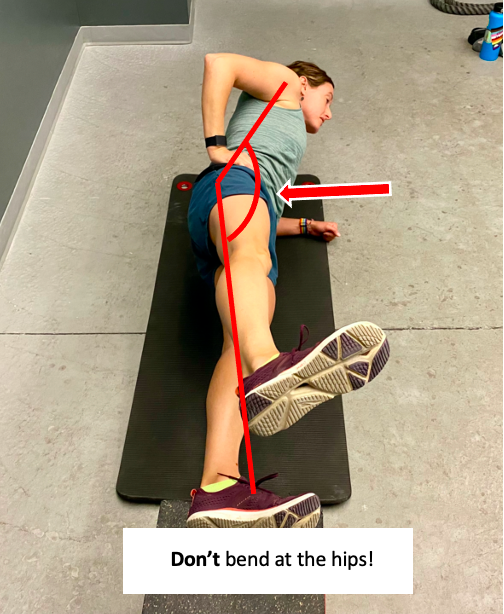

The most common mistake is folding at the waist. Make sure you keep your body in a perfectly straight position. Once you’re unable to maintain this perfectly straight position, stop the timer and record your time.

Medial Chain Test: hold your body in a side plank position with your upper leg on the step and the other leg below the step or with the knee bent. Perform on both sides.

Similar to the lateral chain test, the most common mistake is folding at the waist. Make sure you keep your body in a perfectly straight position. Once you’re unable to maintain this perfectly straight position, stop the timer and record your time.

Posterior Chain Test: while propped up on your elbows, use one leg to push your hips upward until your body is in a perfectly straight line. Perform on both sides.

The most common mistake is allowing your hips to lower. Make sure you keep your body in a perfectly straight position. Once you’re unable to maintain this perfectly straight position, stop the timer and record your time.

Anterior Chain Test: perform a forearm plank with one leg on the step and the other leg hovering. Perform on both sides. This test is usually the easiest for climbers because we tend to strengthen our abdominal muscles most frequently in our training.

The most common mistake is allowing your hips to lower. Make sure you keep your body in a perfectly straight position. Once you’re unable to maintain this perfectly straight position, stop the timer and record your time.

Which exercises should I do to help my medial or lateral chain strength?

Extensive research has been done to identify which exercises most effectively target the medial and lateral chains.⁵ ⁶ Based on the literature and carry over to climbing-specific movements, these are the best exercises to target the medial and lateral chains. You’ll notice that they are the same as the testing positions.

Lateral Side Plank:

Level 1: Hold your body in a perfectly straight line with one leg on the step (same as the testing position). Perform 3 sets.

How long should I hold it? Similar to the concept of “reps in reserve” which is explained in a previous article about strength training for climbers, hold this position until your muscles have 5 seconds of strength remaining (5 “seconds in reserve”). Example: if you could possibly hold the position for 45 seconds before giving out or losing form, hold the position for 40 seconds.

Level 2: Hold your body in a perfectly straight line with one leg in a TRX loop. Perform 3 sets. Hold until your muscles have 5 “seconds in reserve”.

Medial Side Plank:

Level 1 (shortened lever position): Hold your body in a perfectly straight line with the top calf on the step and the bottom leg through the step or with the knee bent (same as the testing position). Perform 3 sets. Hold until your muscles have 5 “seconds in reserve”.

Level 2 (long lever position, also called the Copenhagen Plank): Hold your body in a perfectly straight line with the top foot on the step and the bottom leg through the step or with the knee bent. Perform 3 sets. Hold until your muscles have 5 “seconds in reserve”.

Level 3: Hold your body in a perfectly straight line with the top leg in a TRX loop. Perform 3 sets. Hold until your muscles have 5 “seconds in reserve”.

In conclusion, climbing performance and injury prevention are both influenced by hip/core function. If you are having recurrent climbing injuries to your shoulders, elbows, or fingers, consider that your hip/core strength may be playing a role. If you are experiencing a plateau in your climbing performance, maybe it’s your hip or core weakness that is slowing you down. Try the Bunkie Test to see how your core strength stacks up and if you need to strengthen your medial or lateral chains.

If you are interested in learning more about how the hip/core affects climbing movement and how it could help you with injury prevention or recovery from a current climbing injury please contact Dr. Evan Ingerson at Mend Physical Therapy in Boulder at Evan@mendcolorado.com. Mend is a physical therapy and sports medicine clinic that treats all body regions and people of all athletic abilities, with a specialty in rock climbers and return to climbing programs.

Mend is committed to the health of climbers and our climbing areas and shares the vision of the Boulder Climbing Community. BCC members get their first appointment free and their second appointment 25% off!

Looking for more evidence-based content specifically for climbers? Visit the Mend rock climbing blog, the physical therapy for rock climbers home page, and you can sign up for monthly newsletters to receive the latest evidence-based content about climbing injury prevention, treatment, and training.

References:

Zipser MC, Plummer HA, Kindstrand N, Sum JC, Li B, Michener LA. Hip abduction strength: relationship to trunk and lower extremity motion during a single-leg step-down task in professional baseball players. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021;16(2):342-349.

Robb AJ, Fleisig G, Wilk K, Macrina L, Bolt B, Pajaczkowski J. Passive ranges of motion of the hips and their relationship with pitching biomechanics and ball velocity in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2487-2493.

Beckett M, Hannon M, Ropiak C, Gerona C, Mohr K, Limpisvasti O. Clinical assessment of scapula and hip joint function in preadolescent and adolescent baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2502-2509.

Brumitt J. The bunkie test: descriptive data for a novel test of core muscular endurance. Rehabil Res Pract. 2015;2015:780127.

Boren K, Conrey C, Le Coguic J, Paprocki L, Voight M, Robinson TK. Electromyographic analysis of gluteus medius and gluteus maximus during rehabilitation exercises. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011;6(3):206-223.

Schaber M, Guiser Z, Brauer L, et al. The neuromuscular effects of the copenhagen adductor exercise: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021;16(5):1210-1221.