The Science of the Chicken Wing

Why it Happens and is it Bad for You?

Article by Dr. Evan Ingerson of Mend Physical Therapy

“Chicken-winging” is a movement that every climber experiences. It is defined as a pattern of movement where the elbows raise to the sides instead of being tucked down closer to the chest. This compensation shows up when we’re fatigued and climbing near our limit. We all get told to avoid this position but many of us do not understand why it happens and if it’s truly bad for you. This article will discuss the causes of chicken winging, how it can negatively stress the tissues in our bodies, and give you ways to prevent and avoid chicken winging.

There are two main reasons climbers chicken-wing:

1. Fatigue/weakness in the finger flexors

2. Fatigue/weakness of the scapular retractor muscles.

Let’s talk about the fingers first. Chicken winging from finger fatigue occurs most commonly when we get pumped while sport climbing. The finger flexors are the single most important muscle group for climbing performance. Our fingers inevitably fatigue as we continue to climb or boulder near our limit so our body will start to pull from different areas of the body to get whatever other strength is available. One way to slightly improve the function of the finger flexors is to increase the engagement of the finger extensors.

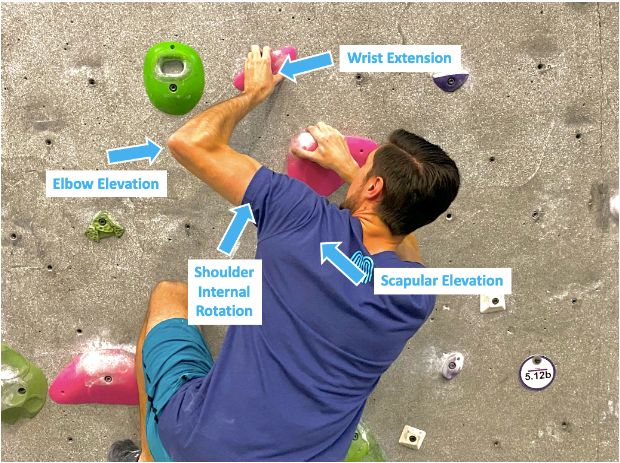

Try this on your own: while keeping your fingers relaxed, cock your wrist backward (toward the back of the hand). You will see that your fingers curl slightly (especially if you have tight forearms!). The technical term for this is tenodesis and that little extra curl of the fingers can assist in crimping and can sometimes be the difference between sending and falling.

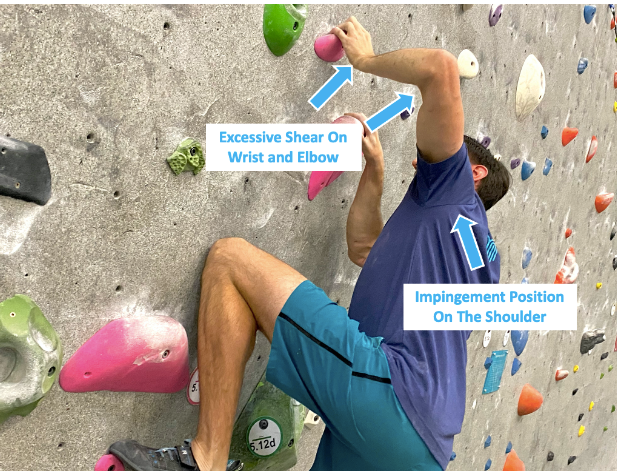

So is it bad for you? This position can change the direction of force on the fingers and can put undue stress on the wrist, fingers, elbow and shoulder. But occasionally using a chicken wing doesn’t necessarily put you at injury risk. According to many studies repetitive stress (overuse) injuries account for up to 85% of all climbing-related injuries. What you’ll want to avoid is repeatedly using the chicken wing position every time you climb as this repetitive stress can lead to injuries. Common overuse injuries that occur from climbing with this movement pattern are medial epicondylalgia and lateral epicondylalgia and can also lead to wrist pain.

Mend Recommendation

Improve the strength and fitness of your fingers flexors using a hangboard and regimented training program which will allow you to climb harder, longer without needing to chicken-wing. Do your best to avoid the chicken-wing position while climbing, but it is ok to use in moderation.

Many hangboard protocols, such as “Max Hangs” and “Repeaters” have been shown in the literature to improve finger strength/endurance and climbing performance. Here are two hangboarding protocols you can try to help improve your finger strength or endurance.

Max Hang Protocol (better for improving strength and also power):

Repeaters Protocol (better for improving endurance and also strength):

Now let’s talk about the shoulder. Chicken winging originating at the shoulder occurs most commonly while bouldering or trying a single or multiple difficult moves at your limit. The primary stabilizer muscles of the scapula during climbing are the upper/middle/lower trapezius and rhomboids, while the primary stabilizers of the shoulder joint are the rotator cuff muscles. When these muscles are strong and not fatigued, they work to maintain the scapula and glenohumeral joint in an optimal position while climbing. As these muscles get fatigued our bodies often compensate by increasing the utilization of the upper trapezius, levator scapula, and deltoid muscles. When this happens the elbows elevate and the chicken-winging begins!

The chicken-wing position can be aggravating to some climbers with shoulder pathology. Shoulder abduction or flexion with combined internal rotation (which is the exact position of the chicken wing) causes compression of the supraspinatus muscle in the subacromial space. In some cases this can lead to rotator cuff tendinopathy and/or shoulder impingement syndrome and this movement pattern is often seen in climbers with biceps tendinopathy. If you develop chronic tendon pain it can be particularly difficult to rehabilitate so prevention is key.

If your chicken winging pattern originates at your shoulder it is more likely to cause injury than if your pattern originates from the fingers. Once again, the occasional chicken wing while pulling a hard move is not likely to cause injury, but repetitive stress on shoulder structures with this movement pattern is likely to lead to pain and injury.

Mend Recommendation

Strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers (primarily middle and lower trapezius) to allow you to climb harder, longer without needing to chicken-wing. Do your best to avoid repetitive stresses of the shoulder in this position while climbing. If you find yourself needing to chicken wing to pull a hard move, it is recommended that you avoid continuing to attempt that move. Go hit the weight room and get those shoulders stronger!

Here are the top 4 exercises (3 for the shoulder and one for the wrist) to help strengthen the muscles that prevent chicken winging.

If you are interested in learning more about how to improve your climbing movement and how it could help you with injury prevention or recovery from a current climbing injury please contact Dr. Evan Ingerson at Mend Physical Therapy in Boulder at Evan@mendcolorado.com. Mend is a physical therapy and sports medicine clinic that treats all body regions and people of all athletic abilities, with a specialty in rock climbers and return to climbing programs.

Mend is committed to the health of climbers and our climbing areas and shares the vision of the Boulder Climbing Community. BCC members get their first appointment free and their second appointment 25% off!

Looking for more evidence-based content specifically for climbers? Visit the Mend rock climbing blog, the physical therapy for rock climbers home page, and you can sign up for monthly newsletters to receive the latest evidence-based content about climbing injury prevention, treatment, and training.